1. Introduction

The purpose of this dossier is to provide some information, according to Old Babylonian administrative and legal texts and letters, for a better understanding of the chaîne opératoire for sesame oil production. It complements the evidence from the Ur III period texts, especially from Irisaĝrig (Dossier A.1.1.12) and Umma (Dossier A.1.1.07). For an overview on places and periods in which sesame oil was produced, see Dossier A.1.1.20.

The process of oil production was brought to light by Stol’s (1985) and Postgate’s (1985) works in Bulletin on Sumerian Agriculture 2 (BSA 2), based on letters and administrative documents from the Old Babylonian period and even texts from later periods, such as medical texts from the Assyrian library in Nineveh, or Neo-Babylonian documentation (Stol 1985). These synthetic works are, above all, commentaries on the subject and not actual reconstructions of the process. Another article, also published in BSA 2 by Stol and Whiting, provides an important edition of an administrative text (BSA 2 180), very useful for understanding the oil-producing process (Stol/Whiting 1985).

The information in the texts also allows us to reconstruct oil milling careers or particular services, such as that of Adda-kala[individual=Adda-kala] in Isin[geogr=Isin] or Balaĝunamḫe[individual=Balamu-namḫe] and Ilī-Ašraya[individual=Ilī-Ašraya] in Mari[geogr=Mari] (see Dossier A.1.1.21).

2. Terminology and Elements for the chaîne opératoire

2.1. Sesame Oil

Logograms i3.giš[glossary=ellum] correspond to sesame oil. Their Akkadian equivalent is ellum, which refers to “sesame oil”, in contrast with the logogram i₃, Akkadian šamnum[glossary=šamnum], which means “oil, fat” in a broader sense but often refers to “sesame oil”.

2.2. Sesame Winnowing

The term našāpum, “to winnow”, is mentioned concerning sesame, for example, in the letter ARM 01 021 from Mari, written by King Samsī-Addu to Yasmaḫ-Addu. Samsī-Addu asks his son to send him sesame, which was already harvested and to winnow it for his meals1Lines 22-25: arhiš ana akāliya šūbilam linaššipū-ma.. Thus, the transported sesame was not winnowed beforehand. It was certainly also the case for sesame used to produce oil.

2.3. Sesame Milling and Oil Production Processes

The Akkadian term for oil milling is ṣaḫātum[glossary=ṣaḫātum] (logogram sur). The writing is always syllabic and never logographic in administrative documentation, in contrast to the function name of oil miller (ṣāḫitum[glossary=ṣāḫitum], written (lu2.)i₃.sur; see infra).

The tools and the techniques used are not strictly related to a “pressing” practice, but rather to a sesame milling process (see below). It is, therefore, more relevant to translate ṣāḫitum as “oil miller” or “oil manufacturer” rather than “oil presser”.

2.4. Dehulling Sesame Seeds

Before milling, sesame seeds could be dehulled to obtain a fine oil. According to Bedigian 2010: 294, the dehulling process by the wet method is in modern China as follows:

1) cleaning the raw sesame seeds;

2) soaking in water at 45–50°C;

3) drying the seeds in an oven at 85–90°C;

4) dehulling and winnowing.

We can assume that the process was similar in Ancient Near East (maybe with alternatives like soaking the sesame seeds in cold water for many hours and drying the seeds naturally in a dry climate).

The process of recovering the dehulled kernels from the water is called ḫalāṣum[glossary=ḫalāṣum] and involves the use of a sack of goat hair (described as para10 a5[glossary=para10 a5] in the documentation of the third Millennium BCE) as a sieve-like (Postgate 1985: 147).

Raw hulled sesame seeds are characterised by a pleasant smell (Bedigian 2010: 86) and were used to produce a fine oil (with a pleasant smell, too, according to the letter AbB 09 058). This type of oil was produced by oil millers (ARM 21 107) in tiny quantities compared to oil produced from whole sesame seeds (ARM 22 276). It was used for food (FM 03 062, FM 03 064, JCS 29 170-183), for anointing (FM 03 029), and as a raw material for the production of perfumed oils (UET 5 769, ARM 21 107) and it is sometimes listed with scented oils (FM 06 059).

2.5. Pounding Sesame Seeds

In a text from Larsa[geogr=Larsa] (YOS 05 204), a quantity of “threshed (dub₂.dub₂.bu, nuppuṣūtum[glossary=nuppuṣūtum]) sesame” is used to produce oil. Nuppuṣūtum is a D/II form of the Akkadian root npṣ, “to crush”, “to pound”. The lexical list Ur5.ra (MSL XI 80, line 79) mentions še.giš.i₃ i₃.dub₂.dub₂.bu, with the akkadian translation nuppuṣūtum “pounded (sesame)”. Perhaps the entry dub2.dub2.bu? is also attested in the Old Babylonian forerunner UM 29-15-641, just after the mention of duḫ.še.giš.i₃[glossary=kupsum] the sesame press cake which corresponds to the remains of sesame after oil milling.

This phrase is also attested in Ur III texts (TCTI 2 04179 from Ĝirsu; Nisaba 15/2 0108, Nisaba 15/2 0515 from Irisaĝrig). The term probably refers to the stage in which sesame seeds were first pounded with millstones (see supra); this could explain why they could transport nuppuṣūtum-sesame.

2.6. Tools Used for Producing Sesame Oil

According to two administrative texts (YOS 12 342 and BSA 2 180) and, to a lesser extent, another document (BIN 07 218) referring to milling sesame oil tools, it is possible to reconstruct the various stages of the chaîne opératoire concerning oil milling in a broad outline (see Stol/Whiting 1985). This summary table mentions the different tools needed per text.

| YOS 12 342 | BSA 2 180 | BIN 07 218 |

| Ceramic vase (dugšagan) for sesame seeds (še.giš.i₃) | – | – |

| – | Vase stand (kannum ša ṣaḫātim) | – |

| Millstone in zubûm-stone (zi.bi) for sesame seeds (še.giš.i₃) | Millstone (na₄ḫar) for sesame oil (i₃.giš) | Millstone (na₄ḫar) for sesame seeds (še.giš.i₃) |

| Wooden mortar (gišnaĝa₄) for sesame seeds (še.giš.i₃) | Wooden mortar (esittum) for sesame oil (i₃.giš) | – |

| Wooden pestle (giš.gan.na) | – | – |

The main difference between the two first documents is that one describes the tools in terms of sesame seeds (YOS 12 342), while the other in terms of sesame oil (BSA 2 180). The focus is not on the same view, but it is quite certain that the objects must have been the same, especially the tools used to mill the sesame seeds.

The text BSA 2 180 states that the tools were rented for four months; this rental amount is equivalent to 4 qa (4 litres) of oil, i.e. 1 qa of oil per month. YOS 12 342 indicates they were rented for one year, but the amount is unfortunately broken.

2.7. Pre-Pounding of Sesame Seeds with a Hard Millstone

Sesame seeds were first pounded with “millstones” (na₄ḫar[glossary=ḫar], Akkadian erûm) made of hard lithic material, like the zi.bi-stone, which is maybe a kind of basalt (YOS 12 342). According to Ur III texts (CUSAS 40-2 0498), a “hand-held stone miller” (šu si₃-ga) supplemented these millstones; a text (CUSAS 40/2 0292) mentions precisely the zi.bi-stone as a millstone intended to pound sesame seeds (for more information, see Dossier A.1.1.12). In BSA 2 180 and BIN 07 218, the lithic material is unfortunately not indicated, but it was certainly basalt. After this first pre-pounding, a kind of paste was then obtained, an agglomerate of pounded seeds, which stuck together thanks to the slightly oily matter of the whole.

2.8. Pounding of Sesame Seeds in a Wooden Mortar with a Wooden Pestle

After pre-pounding with hard millstones, the paste obtained was pounded a second time in a “wooden mortar” (gišnaga₃(gaz), gišnaga₄(kum), Akkadian esittum), equipped with a “wooden pestle” (giš.gan.na, Akkadian bukānum).

2.9. Collecting the Sesame Oil in a Ceramic Vessel Placed on a Vessel Stand

During the second pounding process of sesame seeds in the wooden mortar, the oil miller collected the milled oil step by step in a specific ceramic vessel (dugšagan, šikkatum[glossary=šikkatum]). According to Sallaberger, this vessel is an oil bottle, a kind of ungentarium; the author indicates that the šikkatum was the typical vessel for oil or scented oil in the 3rd and early 2nd millennia BCE (Sallaberger 1996: 107).

This vessel was held by a “vessel stand” (kannum ša ṣaḫātim), probably made of wood, in order to facilitate the oil miller’s operation. Then, during the collecting process, the oil was certainly separated from the “sesame press cake” (tuḫḫi šamaššammī).

3. When Was Sesame Oil Produced?

3.1. Frequency of Oil Production

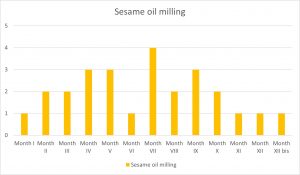

Sesame oil seems to have been produced all year round. In this respect, the expression “old sesame” (še.ĝiš.i₃ sumun) in OrNS 74 327 IB 209 could refer to sesame harvested the previous year, as this document is precisely dated to Month IX/December, just after the harvest of ‘new sesame‘. The data collected through the study of texts clearly referring to the oil milling process is thus summarised in the following table and graph.

| Text | Provenance | Date (original) | Date (BCE) | Months | ||||||||||||

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | XIIbis | ||||

| BSA 2 180 | ? | Si.01?.07.30 | 1749 | x | ||||||||||||

| CT 08 08e | Sippar-Yahrurum | Ad.35.10.02 | 1649 | x | ||||||||||||

| CT 08 36c | Sippar | Ad.08.03.28 | 1676 | x | ||||||||||||

| CUSAS 15 059 | Larsa | WS.04.09.14 | 1823 | x | ||||||||||||

| OrNS 74 327 IB 209 | Larsa | RS.58.09.00 | 1765 | x | ||||||||||||

| ARM 22 276 | Mari | ZL.05.05.02 | 1770 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| KTT 177 | Tuttul | YA.17.07.15 | 1776 | x | ||||||||||||

| YOS 05 093 | Ur | WS.04.09.14 | 1823 | x | ||||||||||||

| YOS 05 204 | Larsa | RS.20.02.05 | 1803 | x | ||||||||||||

| YOS 12 340 | Sippar? | Si.11.04.00 | 1739 | x | x | |||||||||||

| YOS 12 342 | Larsa? | Si.11.05.01 | 1739 | x | ||||||||||||

| YOS 13 359 | Kiš | Ad.37.07.14 | 1647 | x | ||||||||||||

| YOS 13 444 | Dilbat | Sd.14.05.13 | 1612 | x | ||||||||||||

Graph 1. Frequency of Sesame Oil milling in Old Babylonian Texts

Sesame seeds were harvested during Months VII/October-VIII/November (see Dossier A.1.1.17). According to these data, oil production was increasing in Months IV/July and V/August, Month VII/October and Month IX/December; it should be noted, however, that our sample is small as we have looked for explicit occurrences in order to avoid any misinterpretation. The main result is that oil was produced all year round: the study of the document ARM 22 276 from Mari shows that sesame oil can be produced each month, all over the year (see Dossier A.1.1.21).

3.2. Sesame Supplies: Data from the “Oil Bureau” Archive from Larsa

According to Charpin, the “Oil Bureau” Archive from Larsa[geogr=Larsa] was active from the reign of Gungunum to the rule of Sumuel. Among the 67 documents identified in this archive, two administrative texts mention the delivery of sesame in this bureau (Charpin 1976). Only the incoming and outgoing of sesame oil are documented in these documents. YOS 15 087, dated to the reign of Nūr-Adad, which Charpin (2014) identified on the database Archibab as a text from the “Oil Bureau” Archive, has to be added to these documents.

| Text | Date (original) | Date (BCE) | Quantities of sesame seeds delivered (mu.kux) |

| YOS 14 185 | AS.03.07.00 | 1903 | 1095 qa (1095 l) |

| YOS 14 249 | Suel.06.12.00 | 1899 | 133 qa (133 l) + 144 qa (144 l) = 277 qa (277 l) |

| YOS 15 087 | NuAd.C.10.00 | 1867 | 334 qa (334 l) |

In these three documents, the months are not identical: one precedes the harvest (YOS 15 087), while the other two follow it (YOS 14 185 and YOS 14 249; in YOS 14 249, sesame comes from neighbouring towns).

4. Oil Production Specialists

4.1. Oil Millers (ṣāḫitum): Men and Women

Oil millers are mainly referred to by the ideograms i₃.sur; the Akkadian function name, ṣāḫitum[glossary=ṣāḫitum], derives directly from the root ṣḫt, „to mill (the oil)“. There are logographic variants: lu₂i₃.sur in Mari (see Dossier A.1.1.21), Tuttul (KTT 177, see Dossier A.1.1.24), and Sippar (BE 6/1 093); sur.ra is attested only in Damrum (AbB 09 011, AbB 09 125). In the Old Babylonian documentation, the persons designated as oil millers seem to have been male, as reflected in the examples presented in the following table.

| Name | Text | Qualification |

Place | Date (original) | Date (BCE) | |

| Adda-kala | BIN 09 351 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Isin | IE.19.02.17 | 2001 |

| BIN 10 163 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Isin | IE.25.09.00 | 1995 | |

| BIN 10 049 | – | – | Isin | Ši.01.04.00 | 1986 | |

| BIN 10 050 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Isin | Ši.01.07.00 | 1986 | |

| Sîn-iddinam | Gautier Dilbat 6 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Dilbat | SulaEl.14.11.14 | 1867 |

| Ubārum; Ilī-wēdima, Aḫam-arši | YOS 05 040 | arad; guruš ša₃ i₃.sur.e.ne | “servant”; “workers of the oil millers” | Ur | WS.03.07.00 | 1832 |

| Šimut-abī | A 00113 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | ? | WS.07.12.00 | 1828 |

| Ubār-Dumuzi | VS 13 056 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Larsa | WS.11.06.00 | 1824 |

| Nabi-ilišu | TMH 10 205 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Uruk | IRne.20.03.06 | – |

| Sîn-tabbae | tab.ba.ni | “his partner” | ||||

| Ipquša, Aḫu-ṭābum | YOS 05 204 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Larsa | RS.20.02.05 | 1803 |

| Ḫālu-dābiḫ, Balaĝunamḫe’s team: Ilī-ašrāya, Aḫlamu | ARM 22 262

ARM 23 442, ARM 23 443 (duplicate of ARM 23 442) |

lu₂i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Mari | ZL.05.05.15 | 1770 |

| Mūt-ramê | ARM 07 120 | lu₂i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Mari | ZL.xx.12.xx | 1774-1762 |

| Mannum-kīma-Adad and his son dispatched | AbB 09 011 | sur.ra | “oil miller” | Damrum | 00.00.00.00 | 1735-1730 |

| Mannum-kīma-Adad | AbB 09 125 | sur.ra | “oil miller” | Damrum | 00.00.00.00 | 1735-1730 |

| Āpil-Amurru | BBVOT 1 045 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Babylon? | Si.28.03.15 | 1722 |

| Warad-ilišu | CT 08 38a | ṣa-ḫi-tim | “oil miller” | Sippar-Yaḫrūrum | Ad?.00.00.00 | 1683? |

| Bēlī-libluṭ | CT 08 36c | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Sippar-Yaḫrūrum | Ad.08.03.28 | 1676 |

| Tarībum, Manniya, Bēlānum, Sarriqum | CUSAS 29 174 | i₃.sur | “oil miller” | Dūr-Abīešuḫ | Ad21.02.06 | 1663 |

| Qīš-Amurru, Nabium-šēmi, Ilum-šēmi, Ninurta-erībam | sag.ir₃; ma-ḫar PN i₃.sur | “slave”; “in front of PN, the oil miller” | ||||

| Aḫi-wēdum, Ātanaḫ-ilī, Sîn-ibnī, s. Warad-ilīšu | CT 08 08e | – | – | Sippar-Yaḫrūrum | Ad.35.10.02 | 1649 |

| Ibni-Adad, Warad-Kubi, s. Ālī-lūmur | YOS 13 359 | – | – | Kiš | Ad.37.07.14 | 1647 |

| Ilī-erībam | BE 6/1 093 | lu₂i3.sur | “oil miller” | Sippar | Aṣ.03.08.05 | 1644 |

| […]-di | YOS 13 444 | – | – | Dilbat | Sd.14.05.13 | 1611 |

The mastery of techniques for oil milling was handed down from father to son, as was generally the case for craftsmen in Mesopotamia. We can see it in the legal and administrative documentation from Sippar-Yaḫrūrum[geogr=Sippar] (see commentaries of texts CT 08 08e and CT 08 38a), but also in a letter mentioning the sending of an oil miller’s son to mill sesame oil in Damrum[geogr=Damrum] (AbB 09 011).

However, some versions of the Old Babylonian lexical list “Lu” from Nippur (CBS 02241, CBS 10083, N 1850, UM 55-21-291) attest to the existence of oil milling women (munus i₃.sur), directly mentioned after the miller (i₃.sur)2See the composite text in MSL XII 61, lines 789-790 with references in DCCLT: Q000047.. A list of personnel (ARM 22 262) also mentions a woman working in the oil milling service for the Mari palace (see Dossier A.1.1.21).

4.2. Oil millers‘ Status

The Old Babylonian administrative documentation shows that the oil millers and their staffs did not necessarily depend on palaces. For example, while there was an office of oil millers in Mari which directly oversaw royal oil production, a part of this production came from the households of the queen mother and the crown prince, who had their oil millers (ARM 22 276).

There were local productions, such as that of Nanna’s temple of Ur, or Napsuna-Addu’s Princess Iltani[individual=Iltani]’s brother, in northern Mesopotamia. In some “loan texts” from Babylonia, individuals give their sesame seeds to oil millers, who had to produce sesame oil and “measure” it (aĝ₂, Akkadian madādum) after the production (CT 08 08e from Sippar-Yaḫrūrum, YOS 12 340 from Larsa, YOS 13 359 from Kiš[geogr=Kiš], YOS 13 444 from Dilbat[geogr=Dilbat]). The fact that loans of sesame oil milling tools existed (see, for example, YOS 12 342) suggests the exchange of practices and tools between oil millers.

It seems that oil millers were paid in kind. The loan text CT 08 08e from Sippar-Yaḫrurum states that they received 1/3 of the oil production. It is not known whether this wage was standard for the whole of Babylonia. In some cases, old millers could also receive a salary in grain (CUSAS 08 062).

An administrative document from Dūr-abiēšuḫ[geogr=Dūr-abiēšuḫ] (CUSAS 29 174) mentions 4 “slaves” (saĝ.arad, Akkadian wardum) who “were entrusted” (ana maṣṣartim paqdū) to 4 oil millers: thus, an unskilled and unfree worker was assigned to each oil miller to strengthen his working team. Another administrative text from Ur[geogr=Ur] (YOS 05 040) shows a similar situation, this time with 3 workers (guruš, eṭlum) without specifying the exact number of oil millers (maybe 3, if we follow CUSAS 29 174). Another document from Uruk (TMH 10 205) records the receipt of fabrics by an oil miller, accompanied by “his partner” (tab.ba.ni). These workers have therefore to be considered as an additional labour force allocated to oil milling specialists.

4.3. The “House of Oil miller”

A text from Nippur[geogr=Nippur] (TMH 10 126) mentions that a man is given (as a “donation”, a.ru.a) by King Rīm-Sîn and Queen Simat-Ištar to the “house of the oil miller” (e₂.i₃.sur.ra, bīt ṣāḫitim). This expression indeed refers to a workshop specifically intended for oil production. A lexical entry in a manuscript of the Old Babylonian list “Lu” from Nippur (A 30236+) mentions “the chief of the House of oil millers” (ugula e₂.i₃.sur.ra; MSL 12 38, line 157; see also the composite text in DCCLT: Q000047), implying the existence of such workshops. In Mari, these workshops were certainly located outside the palace (see Dossier A.1.1.21).

5. Quantities of Produced Oil and Ratios

The documentation from Babylonia attests to a percentage of about 20%-24% of oil obtained from a number of sesame seeds.

| Text | Sesame seeds quantity | Sesame oil quantity | Percentage of sesame oil per sesame seeds |

| OrNS 74 327 IB 209 | 300 qa (300 l) | 72 qa (72 l) | 24% |

| OBTI 218 | 1 500 qa (1,500 l) | 300 qa (300 l) | 20% |

| UET 5 595 | 120 qa (120 l) | 29 qa (29 l) | 24% |

| YOS 13 444 | 50 qa (50 l) | 10 qa (10 l) | 20% |

| YOS 14 250 | 900 qa (900 l) | 180 qa (180 l) | 20% |

| AUCT 5 99 | 40 qa (40 l) | 10 qa (10 l) | 25 % |

If we consider the average ranging from 20 to 25% oil milled from sesame seeds, we obtain the following data:

| Text | Sesame seeds | Oil to be milled in… | …by | Average of oil milled per day |

| CT 08 08e | 2,700 qa (2,700 l) | 1 month | 3 oil millers | 18 qa (18 l; 6 l per oil miller) |

| YOS 13 359 | 300 qa (300 l) | 10 days | 1 oil miller | 6 qa (6 l per oil miller) |

This average of 20-24% is similar to that from the data in the Mari texts (20%; see Dossier A.1.1.21).