1. Introductory Remarks

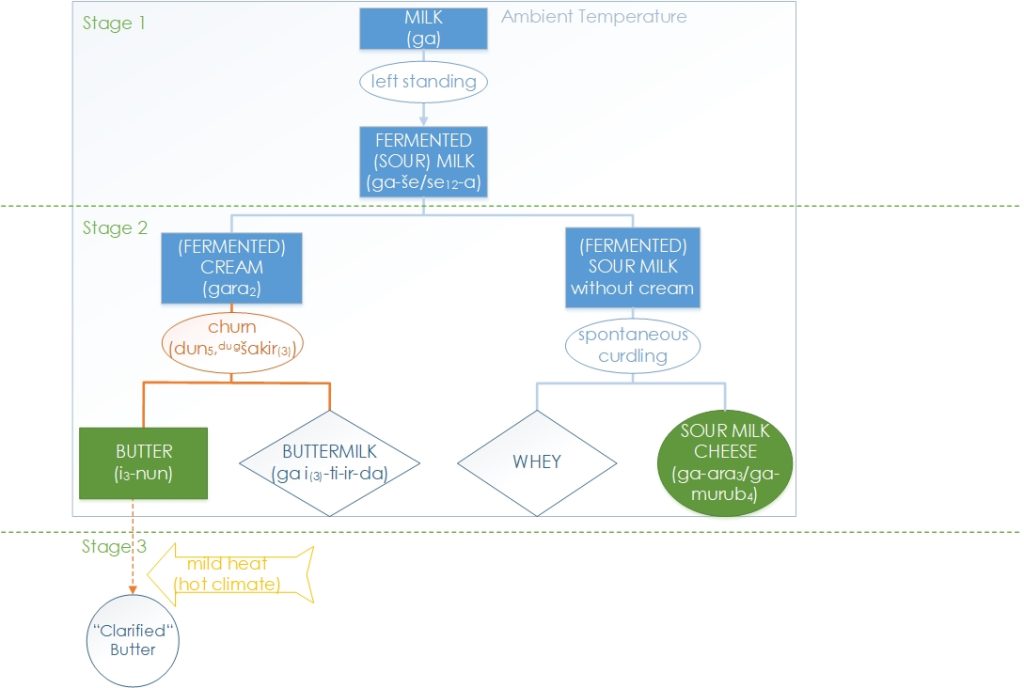

The manufacturing process for dairy products can be reconstructed on the basis of the administrative sources from the third millennium BCE; it discusses how the main dairy products, butter and cheese, manufactured in this period are identified, and the chaîne opératoire will be reconstructed.

According to the available evidence from third-millennium Mesopotamia, dairy products were processed essentially from „cow’s“ (ab2) or „goat’s“ (ud5) milk, while sheep provided wool and were slaughtered to obtain animal fat (Englund 1995: 399 fn. 45; Becker/Benecke/ Küchelmann 2020; Dossier A.2.2.01).1 The exploitation of sheep milk for the manufacturing of dairy products is documented by cuneiform texts only in the Uruk IV-III period, i.e. ca. 3500 – 2900 BCE. See Dossier A.2.1.08. . The manufacturing process of dairy products and their by-products remains largely undocumented by the administrative texts, revealing that it was not of interest to the central administration. This suggests that, unlike sesame and sesame oil which was produced under the direct control of the central administration in the Ur III period (e.g. Dossier A.1.1.12), butter and cheese were manufactured at the herdsmen’s own level and the central administration was only interested in the final products (Dossier A.2.1.02 §1).

Dairy management in the third millennium BCE centred on two main dairy products: „butter“ (Ur III: i3-nun) and „sour milk cheese“ (Ur III: ga-ara3/murub4; Englund 1995: 415). i3-nun[glossary=i3-nun] is to be regarded as fat because, on the one hand, the administrative sources of the Ur III period list it together with other oils and fats; on the other hand, because they summarize it as i3[glossary=i3] „oil, fat“. Because of the element ga[glossary=ga] „milk“ ga-ara3[glossary=ga-ara3]/ga-murub4[glossary=ga-murub4] is undoubtedly a dairy product, too. The two products were made from the same milk batch of milk. In the deliveries of the herders documented in Ur III Umma as well as in Ur[geogr=Ur] or Ĝirsu, there is a constant relationship of 2:3 between the quantities of these two main dairy products „butter“ (i3-nun) and „sour milk cheese“ (ga-murub4). On this basis, one can reconstruct the manufacturing process as described in this dossier.

According to a handful of sources from Puzriš-Dagān, „butter“ (i3-nun) and, in some cases also „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3) were also processed from the milk of wild animals: „wild goats“ (taraḫ) (BIN 3 148; MVN 13 374), „deers“ (lulim) (MVN 13 374), „gazelle“ (mašda) (MVN 13 374) or also from „aurochs“ (am) (BIN 3 148; Hirose 086; PDT 1 371; Princeton 2 041; Babyl. 7 pl. 22 no. 18). The amounts of butter produced from the milk of „aurochs“ (am) registered by these few sources range between 10 litres (Hirose 086) and 82.5 litres (Princeton 2 041), whereas the amounts of „sour milk cheese“ range between 60 litres (Babyl. 7 pl. 22 no. 18) and 120 litres (Princeton 2 041). The relation between the amounts of these two products is about 2:3 (Princeton 2 041; PDT 1 371; Babyl. 7 pl. 22 no. 18). „Butter“ (i3-nun) from „deer’s“ (lulim) milk is attested in very small amounts (e.g., 2.3 litres, MVN 13 374) as it is the case for butter from „wild goat’s“ (taraḫ) milk (e.g., 1.6 litres; MVN 13 374) and from „gazelle’s“ (mašda) milk (1.97 litres; MVN 13 374).

2. The Production of Butter and Cheese: Reconstruction of the Manufacturing Process

Mesopotamian climatic conditions feature relatively high ambient temperatures, and coupled with the absence of refrigeration facilities, milk becomes sour in about 12 to 24 hours (FAO 1990: § 5.1). Natural fermentation was and still is a means to preserve milk from spoiling. Thus many of the processes for traditional dairy manufacturing include a fermentation stage. This stage not only affects the shelf-life of the product but also affects its quality and characteristics (FAO 1990: § 2). Some nomadic pastoral communities of Kenia produce concentrated fermented milk by removing whey „to increase the total solids in the curd“ (FAO 1990: § 5.1.2).

| Sequential Arrangement | Operational Sequence | Data from Sumerian Sources | Ethnographical Parallels |

| Stage 1: Fermented/Sour Milk

(ga-se12-a[glossary=ga-se12-a]/ga-še-a[glossary=ga-še-a]) |

We assume milk with 4 % fat both for bovine and for caprine milk (Park 2017: 44). | In general, the processing of milk into various dairy products, among them prominently butter and cheese, is mentioned in various Old Babylonian literary compositions (VS 10 123; LSU (c.2.2.3); Išbi-Erra E; Dumuzi and Enkimdu (ETCSL 4.08.33)). | |

| The raw milk is left to stand and ferment spontaneously until the fat coagulates. In this primary fermentation stage, the milk is likely to lose some water, which could lead to a slightly higher fat concentration (Dossier A.2.1.04). | See e. g. traditional dairy manufacturing in Jordan Palmer 2002: 184, 192, where milk is placed for fermenting in a container (in the past, a pottery vessel) or in a specially prepared goatskin. Once a skin or a vessel has been used to ferment milk, traces of the bacterial culture remain always present (Palmer 2002: 184, 192) that facilitate fermentation again. | ||

| During coagulation, the fat gathers on the surface and is skimmed off. Consequently, not all the milk is churned for butter production, as is usually the case. | This step is necessary because according to the Sumerian administrative texts, both products – butter and cheese – resulted from the same milk batch2This is indirectly indicated in the balanced accounts on the delivery of dairy products by the herders, where an amount of fermented milk delivered to the central administration is converted into a specific quantity of both butter and cheese, the two main products used as bench-mark for the bookkeeping. See Dossier A.2.1.02 § 2, A.2.1.04 § 1 and MVN 15 108. | See e.g. the production of the Algerian smen (Boussekine/Merabti/Barkat/Becila/Belhoula/Mounier/Bekhouche 2020: 75 § 3.3.1.1). | |

| Stage 2.1. Butter (i3-nun[glossary=i3-nun]) and Buttermilk (i(3)-te-er-da[glossary=i3-te-er-da]) | When churning, the milk fat (cream) separates from the low-fat, watery matter (skimmed milk). Coagulated and acidified milk, i. e. fermented/sour milk, churns into butter more rapidly than sweet milk owing to the lower viscosity of its serum (FAO 1990: § 6.1.7). | According to Sumerian literary texts of the Old Babylonian period, „(sour) buttermilk“ (ga i(3)-te-er-da[glossary=ga i3-te-er-da]) and/or „butter“ (i3) were the result of the „churning“ (dun5[glossary=dun5]) of „milk“ (ga[glossary=ga]) or „cream“ (gara2[glossary=gara2]) (VS 10 123, see Jacobsen 1983; Išbi-Erra E 29-31, Reisman 1976; LSU (c.2.2.3)).

According to Sumerian administrative texts, „Butter“ (i3-nun) was kept in „jars“ (dug, e.g. JCS 24 154 27), in „clay pots“ (dugutul2[glossary=dugutul2], e.g. AUCT 1 320) and various other clay vessels (see more in detail below) as well as in „travel baskets“ made of reed with or without bitumen coat (gekaskal[glossary=gekaskal], e.g. BPOA 1 0658). The fact that the travel baskets for butter were not necessarily always coated with bitumen (e.g., UTI 4 2335) indicates that i3-nun must have been rather solid or, at most, creamy so as not to fall through the small gaps of the braiding. |

Traditionally manufactured butter is often made by churning fully soured (i. e., fermented) cream (FAO 1990: § 6). |

| The residual liquid left is buttermilk (Vaclavik/Christian 2014: 248-251; Velisek 2013: 119). | |||

| Stage 2.2: „Sour Milk Cheese“ (ga-ara3[glossary=ga-ara3]/ga-murub4[glossary=ga-murub4]) | After removing cream for butter, the remaining fermented milk further “matures” thanks to the lactic acid bacteria naturally present in it, and it curdles. This provides the basis for the cheese to be made from it. | Various balanced accounts from Umma, Irisaĝrig and Ur (MVN 15 108; Nisaba 06 20; AuOr 35 107; Nisaba 24 24; SET 130; Nisaba 15/2 1034; UET 3 1215; UET 3 1216; UET 9 0894; UET 9 1026) convert specific amounts of „fermented milk“ (ga-se12-a/ga-še-a) into „butter“ (i3-nun) and „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3/ga-murub4), implicitly indicating that both these products were obtained from fermented/sour milk and hence „sour milk cheese“ was not made out of „buttermilk“ (ga i(3)-te-er-da), the by-product of butter making. | In the traditional dairy production of Jordan, the skimmed fermented/acidified milk (i. e. yoghurt, called laban or imhayḍ) that remains from butter manufacturing is either consumed directly or is also further processed into cheese. For this, it is strained by placing it either in a cloth, in a pit in sandy sediment or in a pot and dried into balls (jamīd), which have a long shelf life (Palmer 2002: 184, 192). |

| The resulting cheese is a sour milk cheese, like e.g., Alpine grey cheese (private communication of J. Peters and E. Märtlbauer) or also the german „Harzer-Käse“, actually a by-product of butter production. | Cheese obtained from skimmed sour milk can be compared to whey cheese in terms of low-fat content (e.g. Italian ricotta or Turkish lor). | ||

| At high ambient temperatures, this stage neither requires rennet for coagulation to obtain clots of solid cheese nor extra heating to remove moisture from the watery mass. | No evidence of rennet nor of the use of heat to produce „sour milk cheese“ according to the administrative sources. | In the traditional dairy production of Jordan, extra heating is not always required for the production of cheese from skimmed acidified milk depending on climatic conditions (Palmer 2002: 184, 192).

Similarly, also the šīrāz cheese in Luristan and kama cheese in northeastern Persia are obtained without heating by putting the buttermilk in a skin and allowing the curds to precipitate (Balland 1992, also available online here). |

|

| Stage 3: From Butter to Ghee or Clarified Butter | Butter contains around 80% fat, ca. 2% non-fat components (proteins, carbohydrates and other substances), and the rest (ca. 18 %) is water. | ||

| However, water in butter facilitates oxidation leading to rancidity. To avoid this, water must be forced off from butter as much as possible, leaving almost pure butter oil, i.e. ghee (379-380 Englund 1995; Boussekine/Merabti/Barkat/Becila/Belhoula/Mounier/Bekhouche 2020: 75 § 3.3.2; Sserunjogi/Abrahamsen/Narvhus 1998). | No evidence of this stage in the administrative sources. | This is traditionally done by heating butter in vessels to temperatures between 40°C and 120°C (mostly 110-120°C) by constant stirring to prevent scorching (FAO 1990: § 6 table 19). | |

| When consumed, rancidity in butter does not seem to pose a health hazard, but it rather seems to be just a matter of taste and odour. | Many societies still use and praise rancid fats today, e. g. salted smen in Morocco (Deeth/Fitz-Gerald 2006: 481ff., 513-516, 517ff.). |

3. The identification of the main dairy products: butter and cheese.

3.1. What is i3-nun?

i3-nun is a fatty substance derived from „fermented milk“ (ga-se12-a[glossary=ga-se12-a]/ga-še-a[glossary=ga-še-a]). i3-nun literally means „princely fat, oil“, and in the Presargonic and Sargonic periods, primarily designated butter from goat milk (Dossier A.2.1.06, Dossier A.2.1.07). In Ur III Ur and sometimes also in Umma, i3-nun was often abbreviated to i3 „fat, oil“ (e.g. UET 3 1214). Like other fats, i3-nun was used for the production of scented oils, among them i3-nun du10-ga[glossary=i3-nun du10-ga] „scented butter“ and i3-nun ḪA „…“ (Dossier A.4.X).

According to Sumerian literary texts of the Old Babylonian period, „(sour) buttermilk“ (ga i(3)-te-er-da[glossary=ga i3-te-er-da]) and/or „butter“ (i3) were the result of the churning of „milk“ (ga) or „cream“ (gara2[glossary=gara2]) (VS 10 123, see Jacobsen 1983; Išbi-Erra E 29-31, Reisman 1976). According to Sumerian administrative sources, „butter“ (i3) together with „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3/ga-murub4) was delivered by cows’ and goat’s herders as a share of their dairy products. In this respect, i3-nun „butter“ is one out of many dairy products documented in the administrative texts of the Ur III period, such as „cream“ (gara2, Dossier A.2.1.04), „sour milk“ (ga-se12-a/ga-še-a) or „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3/ga-murub4). In particular, various balanced accounts from Umma and Irisaĝrig document the expected yield rate of „butter“ (i3-nun) and „sour milk cheese“ (ga-murub4) from „fermented milk“ (ga-še-a[glossary=ga-še-a]/ga-se12-a[glossary=ga-se12-a]): 5 % (= 1/20) of the fermented milk volume for „butter“ (i3-nun) and 7.5 % (1/13.3) of the fermented milk volume for „sour milk cheese“ (ga-murub4) per „cow“ (ab2 maḫ2) or „nanny goat“ (ud5) per year (MVN 15 108; Nisaba 06 20; AuOr 35 107; Nisaba 24 24; SET 130; Nisaba 15/2 1034). If we assume milk with an average of 4 % fat both for bovine and for caprine milk (Park 2017: 44), out of 100 litres of fermented/sour milk, one would obtain ca. 4 litres of pure milk fat, but ca. 5 litres of butter with an average of 80 % fat. Despite the fact that we cannot reconstruct the exact composition of the product i3-nun manufactured by the herders in Sumer and that its exact fat percentages very likely fluctuated depending on various processing conditions, these figures strongly support the identification of i3-nun with butter rather than ghee, which would require a much higher concentration of fat in the starting fermented/sour milk (ga-se12-a/ga-še-a; see the calculations illustrated below in fn. 3). It is important to note, however, that higher yield rates were expected from „fermented milk“ (ga-se12-a) in Ur during the reign of Ibbi-Suen (see Dossier A.2.1.04): 6.5 % (= 1/15) of the milk volume for „butter“ (i3-nun) and 10 % (1/10) for „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3).

„Butter“ (i3-nun) was kept in „jars“ (dug[glossary=dug], e.g. JCS 24 154 27), in „clay pots“ (dugutul2, e.g. AUCT 1 320) and other clay vessels (duggir3[glossary=duggir3]/gir13[glossary=duggir13]/gir16[glossary=duggir16]; dugkur[glossary=dugkur]; dugkur-ku.du3[glossary=dugkur-ku.du3]/ku-kur-du3[glossary=dugku-kur-du3]; (dug)gur4-gur4[glossary=(dug)gur4-gur4]/gur8-gur8[glossary=duggur8-gur8]; dugniĝ2-banda3[glossary=dugniĝ2-banda3]; dugsab[glossary=dugsab]; (dug)saman4[glossary=(dug)saman4]; dugumbinx[glossary=dugumbinx]) as well as in „travel baskets“ made of reed with or without bitumen coat (gekaskal, e.g. BPOA 1 0658). Often these vessels were closed with a leather cover (e.g., dug: MVN 16 768, Nisaba 15/2 0478; dugniĝ2-5-sila3: Nisaba 24 02), very likely to prevent oxidation of the butter or sheltered in a leather bag (saman4: Santag 6 011), likely for better preservation during transport or storage. In particular, the fact that the travel baskets for butter were not necessarily always coated with bitumen („travel baskets“ gekaskal[glossary=gekaskal], e.g., UTI 4 2335) indicates that i3-nun must have been rather solid or at most creamy, so as not to fall through the small gaps of the braiding. This evidence speaks again in favour of the identification of i3-nun with „butter“, likely still a more solid product (Deimel 1926: 10ff) than ghee under the climatic conditions of Mesopotamia, pace the hitherto commonly accepted interpretation as „ghee“ or as „clarified butter“ (Englund 1995; Stol 1993; Stol 1997; Butz 1973/74: 37ff followed by Foster 1982: 166 fn. 70 and recently also by Widell 2020: 134-1373Widell (2020: 134-137, exp. 136) assumes that i3-nun is to be identified with ghee featuring 99 % of fat just because unrefrigerated, (fn. 16) „unsulted butter typically develops slightly off to rancid flavours in 4-7 days (…). This rancidity is the result of fat oxidizing, and would be further accelerated by the exposure of the butter to air and the higher average temperature of southern Mesopotamia“. In this respect, one has to note that vessels storing butter were often closed by a leather cover, very likely to prevent oxidation (see above). Moreover, rancidity is still nowadays mostly only a matter of taste and odour and does not seem to represent a health hazard (Coultate 2002: 97-98). Instead, many societies praise rancid fats as delicacies, like, e.g., the Algerian smen (Boussekine/Merabti/Barkat/Becila/Belhoula/Mounier/Bekhouche 2020: 75 § 3.3.1.1; Deeth/Fitz-Gerald 2006: 481ff., 513-516, 517ff.). Furthermore, the Sumerian administrative sources do not allow for reconstructing the exact composition of the dairy products they document. Indeed, the concentration of fat, solids and moisture in these products may have varied depending on the expertise of the herder, the seasonal fluctuation of milk production by the animals and current climatic conditions. Widell suggests (2020: 135) to identify ga-se12-a in the Ur III period as a (low fat) sour cream with allegedly a fat content of 7-8 % (approximately twice as high as in the raw milk) based on his identification of i3-nun with a 99% fatty substance, i.e. ghee, and solely taking into account the conversion rates (i.e. expected yield rates) of ga-se12-a into butter and cheese attested in Ur during the reign of Ibbi-Suen (he, however, omits to mention the same product attested as ga-še-a in Umma, Irisaĝrig and Ĝirsu). These expected yield rates amounted, respectively, to 6.5 % (= 1/15) of the fermented milk (ga-se12-a) volume for butter (i3-nun) and 10 % (= 1/10) of the milk volume for „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3; more precisely, according to these yield rates and ghee with 99 % of fat, the base product ga-se12-a would require 6.44 % of fat, not 7-8 %). However, as seen above, various balanced accounts from Umma and Irisaĝrig document even lower expected yield rates during the Ur III period: 5 % (1/20) of the milk volume for butter and 7.5 % (1/13,3) of the milk volume for „sour milk cheese“, which instead fit very well with the identification of ga-se12-a/ga-še-a as fermented/sour milk with 4% fat and i3-nun with butter featuring an average of 80 % fat (e.g., MVN 15 108, SET 130, Nisaba 15/2 1034 and Dossier A.2.1.02). Should we still follow Widell’s identification of i3-nun with ghee at 99% fat, these lower yield rates would call for a ga-se12-a (and ga-še-a) with at least ca. 4.95 % of fat. Herewith, ga-se12-a would feature a fat percentage of ca. 4.95 % in Umma and Irisaĝrig and later of ca. 6.44 % in Ur.).

3.2. Butter vs. Ghee

If subjected to heating, butter could also have been processed into ghee, i. e. clarified butter, in order to avoid rancidity (Stage 3 above; Matissek 2019: 570; Sserunjogi/Abrahamsen/Narvhus 1998). Though there is hardly evidence for this stage of the manufacturing process in the administrative texts (Stage 3 above). One text mentions the delivery of fuel for the processing of butter and „honey“ (lal3), but this text very likely documents a further treatment of already manufactured butter (and honey), possibly for the preparation of sweet dishes or the manufacture of scented oils (BPOA 1 1659). Given the rarity of wood or reed fuel, butter could have been heated together with the baking of bread and/or cooking of soup at household level (see the simultaneous baking and cooking with the same fuel in Brunke 2011: 185, 186-189, 220). But this is neither documented by the administrative sources. Due to its specific calorific values with respect to reed or wood (Deckers 2011) and its use mostly for non-kiln firings (Sillar 2000: 46), dung fuel might have suited well for the manufacturing of ghee out of butter.4It is worth noting that dung is one of the most widely used fuels for non-kiln firings in countries that feature a long-lasting tradition of ghee manufacturing, e.g. India and Pakistan as well as Africa (Sillar 2000.46; FAO 1990: § 6 table 19). According to Sillar 2000: 46 and Deckers 2011: 143, herbivore dung burns steadily and evenly, and it is still possible to achieve a relatively stable high temperature also within open firing. An experiment of dung-fuelled fires in Egypt with local village-made dung cake fuel (using palm fronds for initial tinder) produced a maximum of 640 degrees C in 12 minutes, falling to 240 degrees C after 25 minutes and 100 degrees C after 46 minutes. These temperatures were obtained without refuelling and without bellows (Samuel 1989: 276). The use of dung as fuel is never explicitly documented by the cuneiform sources from Mesopotamia, as one would expect from the documentation produced by central organizations and not from the herders themselves. Though, „in semi-arid and arid regions, many scholars emphasize the potential contribution of dung fuel burning“ and „dung fuel use has been inferred based on ethnoarchaeological comparison“ (Proctor/Smith/Stein 2022: 5). Besides its exploitation as fuel, dung suited for various other uses, like the manuring of fields (Styring/Charles/Fantone/Hald/McMahon/Meadow/Nicholls/Patel/Pitre/Smith/Sołtysiak/Stein/Weber/Weiss/Bogaard 2017), and its use is always limited to the quantity produced daily by the livestock. Nevertheless, according to Laugier et al. (2021: 13), dung was available in great quantities because sheep and goats produce an average of 500 and 300 pellets per animal per day, respectively. Dung was considered, together with wood, reeds and grasses, an important source of fuel for both northern and southern Mesopotamia, according to Matthews (2010: 106), and it was sometimes preferred to other types of fuel despite its availability (Deckers 2011: 143, 153). At Abu-Salabikh, the differences in the type of fuel used in different hearths, ovens and rooms of ca. 2500 BCE „suggests there was a range of considerations in the selection of fuel for different installations and contexts“ (Matthews 2010: 107). In particular, the chambered oven of room 69 is interpreted as the principal food-cooking and preparation area and featured sheep and goat dung pellets. On the other hand, the analysis of wood-and-dung-containing assemblages from tannurs in middle Khabur sites dating from the 5th to the 3rd millennium BCE featured a higher percentage of wood in the 3rd millennium-tannurs compared to the 5th-millennium ones (McCorriston 2002: 490). According to McCorriston, this data is to be interpreted as a greater use of wood fuel in 3rd-millennium tannurs than dung fuel in the Khabur valley. Notwithstanding all this, the assumption that herders in the countryside would have had appropriate cooking vessels for ghee is not supported by any administrative or literary source. In this regard, a passage of the Cylinder B of Gudea listing various foodstuffs defined as „it is the food of the gods“ (niĝ2-gu7 diĝir-re-ne-kam, RIME 3/1.01.07.CylB iii 23) offers a detail that might confirm that the manufacture of butter did not require any extra heating: „honey, butter, grapes, fermented milk … (they are all) things untouched by fire“ (lal3 i3-nun ĝeštin ga-še-a … niĝ2 izi nu-ta3-ga, RIME 3/1.01.07.CylB iii 18-22).

Possibly ghee or clarified butter could also have been obtained without extra heating, simply by means of high ambient temperatures under hot climatic conditions (also note the remark of Deimel 1926: 10 about butter being almost fluid during summer). Indeed in southern and eastern Africa, an intermediate product between butter and ghee, called nigour kibe „melted butter“, is made using only mild heat (about 40°C). This product contains about 10 % moisture (compared to 20 % in butter) and can be kept at normal room temperature for about 6 months without developing noticeable rancidity (FAO 1990: § 6 table 19). Such a process is not expected to be documented by the hitherto available administrative sources.

Details of butter, buttermilk and cheese production occur instead in an Old Babylonian literary text describing pastoral life: a Dumuzi lament (VS 10 123, Jacobsen 1983).

3.3. What is ga-ara3/murub4?

The term ga-ara3 identifies „sour milk cheese“, i.e., cheese obtained from the natural curdling of fermented milk after the cream is skimmed off for butter production (Stage 2.2 above; Englund 1995: 3805Widell (2020: 134) recently stated that „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3) „was produced from the fermented buttermilk, which typically contains about 0.5-1% fat“. However, various balanced accounts from Umma, Irisaĝrig and Ur convert specific amounts of „fermented milk“ (ga-se12-a/ga-še-a) into „butter“ (i3-nun) and „sour milk cheese“ (ga-ara3/ga-murub4), implicitly indicated that both these products were obtained from fermented/sour milk (see above the reconstruction of operational sequence) and hence „sour milk cheese“ was not made out of „buttermilk“ (ga i(3)-te-er-da). Indeed, ga i(3)-te-er-da is identified as „buttermilk“ because it is mentioned as the residue of the churning of milk in a Dumuzi lament (VS 10 123 Col. iv 4, see Jacobsen 1983: 196): „making the buttermilk leave the butter as were it clay (sediment after the flood)“ (ga i-te-er-da im-gen7 i3 in-taka4-e). Furthermore, „buttermilk“ (ga i(3)-te-er-da) is twice attested in the administrative texts from Ur (UET 3 1219 o. 3 and UET 9 0825 o. 7), one of them clearly differentiating it from „fermented/sour milk“ (ga-se12-a: UET 9 0825 o. 7). This, together with the proportions given for both products, confirms that the conversion given by the balanced accounts is based on empirical data.). The term ga-ara3 includes the lexeme ga „milk“, whereas the element ara3 remains unclear. In Ĝirsu, Ur and sometimes also in Umma, ga-ara3[glossary=ga-ara3] was often abbreviated to ga „milk“; in Umma, it was named ga-murub4[glossary=ga-murub4] (muru2; „ud-gunû“), literally „medium milk“. In the Sumerian terminology and according to the hierarchically ordered lists in administrative documents, i3-nun „butter“, literally „princely oil“, represented the best dairy product, while ga-murub4 „sour-milk-cheese“, literally „medium milk“, represented the average dairy product.

„Sour milk cheese“ was manufactured from skimmed sour milk via natural fermentation and natural coagulation thanks to the relatively high ambient temperatures in Mesopotamia and the lactic acid bacteria naturally present in the milk. As already mentioned above, in this stage, no starters or rennet nor extra heating are required. The result can be compared to the acid-coagulated cheeses of central Germany, known as „acid curd“ or „Harzer-Käse“, which are produced from acid curd quark, and quark is manufactured from acid-coagulated milk with or without the addition of rennet. The cold fermentation occurs at a temperature of 21-27 °C for 15-18 hours. After cutting and stirring, the curd sinks to the bottom, and the whey is removed. The subsequent maturation takes place at temperatures between 22°C and 24°C for 48-72 hours, then between 16°C and 19°C (Hartmann et al. 2018: 436-437; Bintsis/Papademas 2018: 131-132).

There is no evidence that herders used any kind of rennet, be it the stomach of young animals or plant-based. Herders were the principal suppliers of dead and slaughtered animals for the provincial administration of Umma (Stepien 1996: 199), though there is no evidence that they also dealt with parts of the slaughtered animals and/or meat (Stepien 1996: 97). Instead, according to Stepien (1996: 199) there was a so-called „meat distribution agency“ to which herders delivered the entire dead or slaughtered animals. This confirms, that herders may have occasionally had access to parts of slaughtered animals, but not on a regular basis. Therefore, the stomachs of young animals were not constantly available to them to use regularly as rennet for cheese making. Neither is there any evidence that herders had the specific vessels required to heat the curds.